Weightier, More Numerous Vehicles Spur Work to Make Surfaces Less Noisy; One Test Highway Is 'Like Driving on Carpet'

By SHIRLEY S. WANG

Engineers and scientists in several states are trying to pave the way to a quieter future,experimenting with rubber, asphalt and gravel in search of a way to make roads less noisy.

Virginia is testing several stretches of experimental pavement as part of a $7.5 million state project. Arizona and California have been trying different roadway surfaces meant to reduce noise. Washington state, which has sampled several surfaces with limited success, is pushing ahead with others.

So far, efforts in the field of so-called quiet pavement are showing mixed results. Some surfaces can be more costly to put down than traditional roadways and tend to require more frequent repairs, according to pavement engineers. Other experimental surfaces

have broken down over time and ultimately become even noisier than the original pavement they replaced.

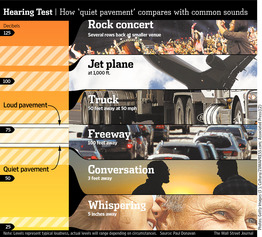

The motivation to make roads quieter is great. The sound of highway traffic about 50 to 100 feet away—a common distance between homes and highways—typically runs 65 to 75 decibels, about the volume of a normal conversation heard three feet away, said Paul Donavan, a senior scientist at Illingworth & Rodkin Inc., a firm specializing in acoustics and air quality.

Trucks are about 10 decibels louder than cars, said Dr. Donavan, who has a doctorate in acoustics from Massachusetts Institute of Technology. An increase of 10 decibels corresponds to a doubling in loudness to the human ear.

Traffic noise has become more of a problem in some communities because there are more cars on the road, and heavier vehicles

altogether, as well as vehicles driving at higher speeds.

The noise stems in part from car engines, wind and other factors, but when vehicles drive at speeds of 60 miles per hour or greater, road noise results primarily from contact between the tires and the roadway, according to Dr. Donavan.

For residents who live near busy highways, the noise is disturbing and may be harmful to their health. It also lowers property values and necessitates costly noise barriers. Engineers say newer pavements could reduce sound by three to five decibels, an audible difference.

Roads generally are paved with concrete, a rigid surface made of stone and sand and bound with cement. Or they are paved with asphalt concrete, a more flexible surface in which the binder of the stone and sand is asphalt, the sticky substance left after oil has been refined.

The noise level of a road depends on three factors: the texture of the road surface; its stiffness; and its porosity—how big the air holes are. Too smooth a surface isn't good because it can cause squeaking, but too bumpy a surface causes rumbling.

One trick for quieting pavement is to give it a "negative" texture, or small divots and gouges, according to Robert Rasmussen, a pavement engineer at Transtec Group Inc., a pavement-engineering and design firm.

But if those divots get clogged, the sound reduction is erased. In Europe, where the European Union has mandated that metropolitan areas use quieter pavement, a giant vacuum-cleaner-like device is used to suck the grit out of the roadway divots, according to researchers.

Engineers have explored using different materials, such as bits of rubber or smaller stone mixtures, to reduce noise. They also have looked at the direction, depth and spacing of the lines that are used to increase friction in concrete roads. Striations that are threequarters of an inch wide and 1/16 to 3/16 of an inch in depth appear to be quietest, Mr.Rasmussen said.

Near Hunts Point, Wash., an exclusive community of mostly waterfront homes across a heavily trafficked bridge from Seattle, road noise was reduced by four decibels after a nearby highway was paved with quiet asphalt in 2007, said Tim Sexton, manager at the state Department of Transportation's Air Quality, Noise and Energy Policy.

Local drivers were enthusiastic at the time: "It's like driving on carpet," said one, according to a community newsletter.

However, any muffling effect was gone within six months, according to Mr. Sexton. In fact, the asphalt surface, which used techniques such as more negative texture, has actually become louder than standard pavement over time as the divots became filled with grit.

The pavement, which also deteriorated faster than regular pavement, won't be used on the rest of the highway, Mr. Sexton said. Because of the deterioration of the material, a cleaning vehicle wouldn't have been helpful in maintaining the quietness of the road, he said.

Washington state hasn't given up, however, and is still testing other sections of quiet pavement around the state, including five types of quiet concrete with different surface textures. "It doesn't seem like the pavement types that we've tested are going to work for the types of roadways we've tested them on so far, but we're going to continue researching it until all the sections have been replaced," Mr. Sexton said.

Write to Shirley S. Wang at shirley.wang@wsj.com